What is really going on with Youth Crime?

Youth Crime has long been a hot button topic in the news cycle. There is fear mongering, sensationalism and general misrepresentation of statistics to paint the picture of a country in crisis, with youth running wild and making us unsafe in our homes.

But how accurate is this picture? And what does fear mongering achieve? Is there a better approach to preventing youth crime?

The data

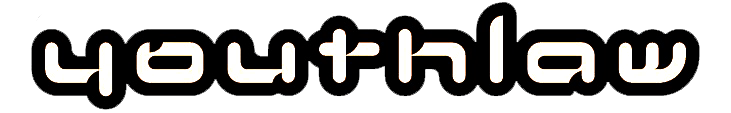

Youth crime rates are falling across the board in Australian states and territories and have been falling for more than a decade.

(Data from Criminologists debunk claims of ‘youth crime crisis’ as data shows dramatic declines – ABC News)

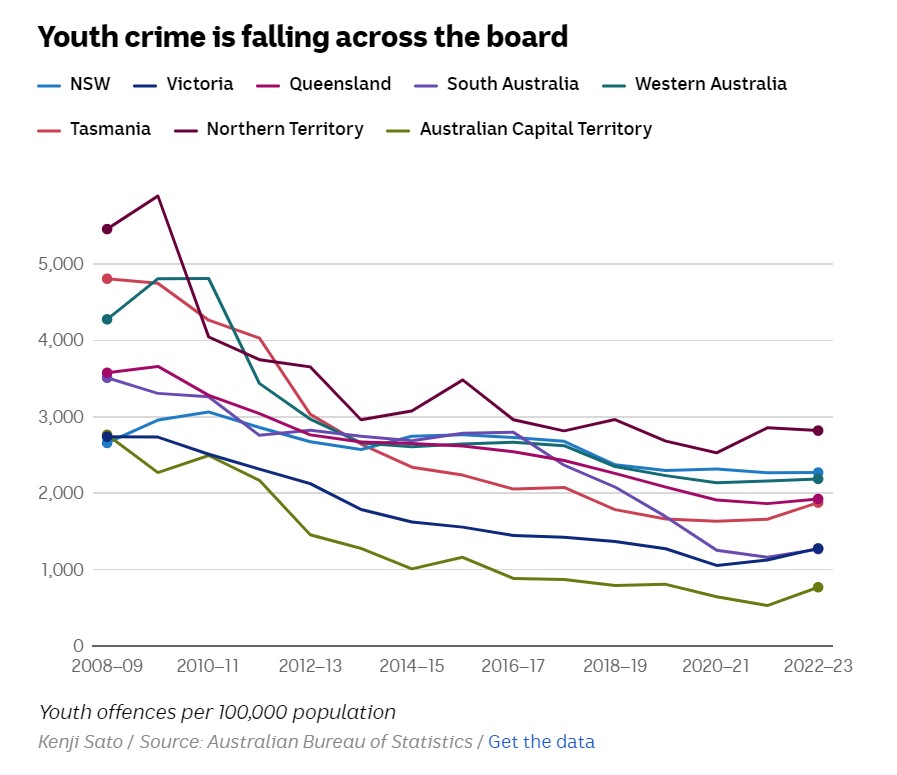

There is also data which shows that youth crime is reducing faster than adult crime, throwing the narrative that youth crime is the biggest threat to our safety on its head.

(Data from Criminologists debunk claims of ‘youth crime crisis’ as data shows dramatic declines – ABC News)

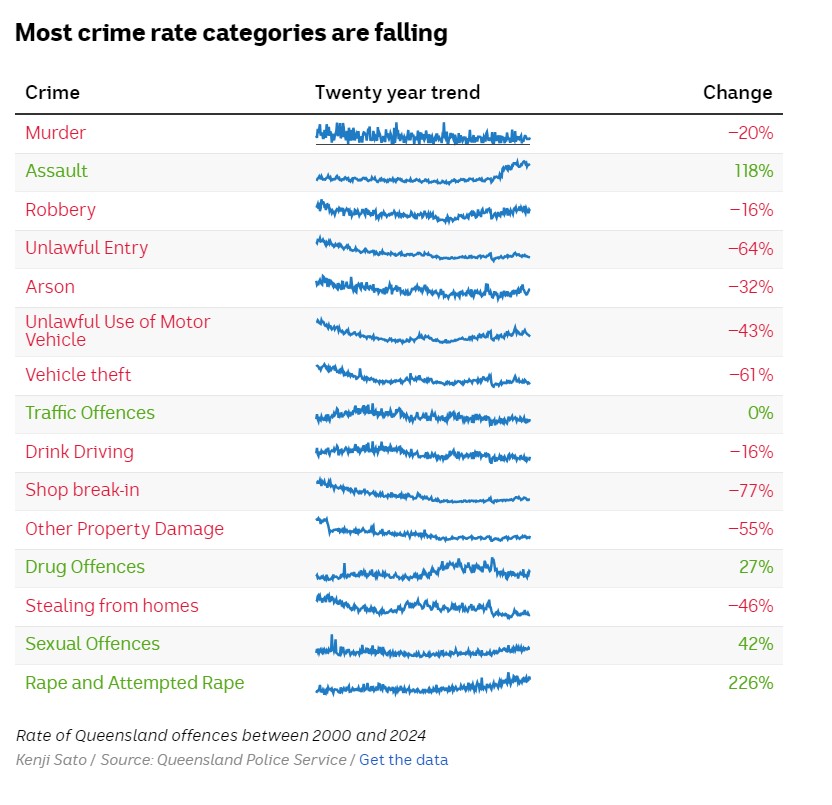

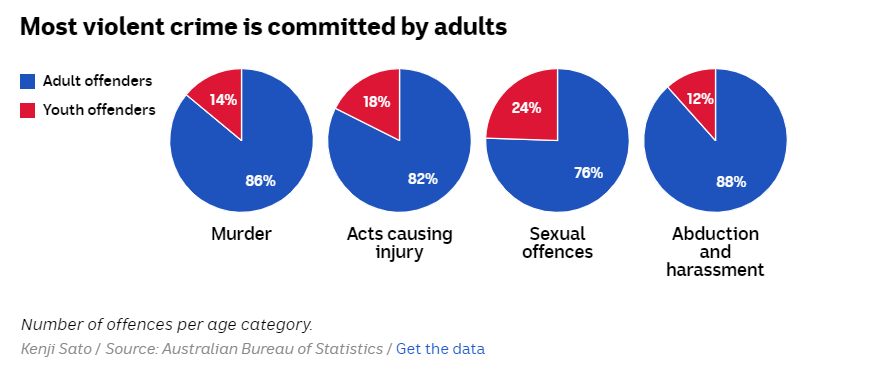

The data shows that in relation to Queensland there has been significant decreases in a number of crimes with notable exceptions including rape, domestic violence and assault. What is also notable is that the vast majority of these kinds of violent crimes are committed by adults.

(Data from Criminologists debunk claims of ‘youth crime crisis’ as data shows dramatic declines – ABC News)

(Data from Criminologists debunk claims of ‘youth crime crisis’ as data shows dramatic declines – ABC News)

What does fear mongering achieve?

When the news reports on youth crime as if it is increasing at rapid rates, that it is getting more prevalent and more violent, it leads to harsh and draconian policy responses which we can see occurring in different Australian jurisdictions.

- The LNP in Queensland has promised to deliver harsher penalties to youth offenders with the slogan “adult crime adult time” becoming the centrepiece of its election campaign.

- Labor in Queensland has watered down detention as a last resort protections, toughened youth bail laws and promised to built more youth detention centres.

- Victoria has reneged on its promises to reinstate the presumption of bail for under 18s and to raise the criminal age of responsibility to 14.

- Northern Territory has gone entirely backwards and is looking to reinstate the criminal age of responsibility as 10 years old.

As the data indicates, the reality facing us is that while the population has continued to grow, we have actually seen the number of offences stay the same or decrease in certain areas. There is no increase in youth crime which is supported by the data.

The ABC discussed the matter with Griffith University criminologist Ross Homel who said that the idea that harsher penalties would reduce youth crime was a lie perpetuated by the major parties. He said that the opposite has been repeatedly demonstrated through twin studies, randomised controlled trials, natural experiments and longitudinal studies, “criminal justice processing of juveniles is itself a cause of future offending. It doesn’t make the community safer.”

The popular punishment-based policy approach fails to address the underlying causes of youth crime, which include neurodevelopmental disability, sexual or physical violence, poverty and low education.

Is there a better approach?

Neurological and other scientific studies on children show that their brains continue developing even up to the age of 25, and this makes children and young adults prime candidates for rehabilitation. We know that early intervention and working with communities improves outcomes for children and the community. Preventing children from entering into the criminal justice system, prevents them from becoming entrenched in the system and potentially becoming repeat offenders. It is at this point that they become increasingly dangerous to the community. If we focus on early prevention, and diverting children away from the criminal justice system, we are giving them a better chance to rehabilitate and become productive within society and protects the community better in the long-term.